How to understand something intuitively? 🌱

Working as a product manager means that I constantly come across new topics and concepts that I need to absorb.

Sometimes it’s just about quickly acquiring the knowledge necessary to complete a specific task. In those moments, I don’t try to build deep competence about something – the bare minimum is enough to move forward. I know I won’t return to that knowledge anytime soon, so the goal here is to learn only as much as I need and select the knowledge I need to absorb with surgical precision – not a bit more.

But there are areas where the stakes are different. In those, I don’t just want to “get by,” I want to become really good at what I do. And in that case, quick optimization for the immediate goal isn’t enough. I seek an understanding that is intuitive, naturally present in the way I think and act.

We live in exciting times for people who like to learn on their own. Language models can patiently and thoroughly explain everything we still feel uncertain about. In a world where access to knowledge has never been easier, the key question becomes: how can we learn in a way that allows that knowledge to truly take root?

That’s why I treat this post as my “blueprint” for intuitive learning – a map I can use anytime I pick up a book, start a tutorial or open ChatGPT to consciously, strategically take the next steps until understanding begins to form into a coherent whole.

What is intuitive understanding?

We can understand a concept in different ways:

- Shallow understanding – I can repeat the definition and recognize the phenomenon. Encountering the concept doesn’t surprise me; I have a rough sense of how it works, but passively – I can’t freely reproduce the definition or explain its use in context. I need to actively recall the mechanism and I may forget the thing even exist if I don’t see it in my environment often.

- Deep understanding – I can apply it in practice. I see the input/output structure, I understand its links with other concepts, I can formulate a correct definition on my own, and I feel confident about it.

- Intuitive understanding – I feel how it works, even without formulas or instructions. I can recognize different forms of the phenomenon’s “expression” in the world and transfer the concept between domains, applying it in new situations. It never slips out of my mental network, I can not only passively recognize the concept but I can use it actively as I try to process new information.

I want to unpack the process of reaching the level of intuitive understanding, so that every time I know exactly how to approach it step by step.

Full disclosure – I explored this topic (“what does it mean to understand something intuitively?”) together with ChatGPT – the stages below are the result of our joint discussions on how to build such understanding step by step.

To ground this in something concrete, I’ll take a fresh example from yesterday: trying to understand what an SDK (software development kit) is.

Building intuitive understanding

0. Definition

The first step is to reach for a definition. According to Wikipedia: An SDK is a set of tools for developers necessary to create applications that use the functionality of a given library (e.g., Java Runtime Environment) for a specific platform (e.g., Android operating system), hardware (e.g., GPS module), etc.

An SDK usually includes:

- documentation

- header files for the given programming language

- sample source codes

- compiled libraries (in the case of an SDK for a library)

- the library’s source code (depending on license and SDK type)

At this stage, it’s good to try to paraphrase the definition in your own words.

My current understanding is this: An SDK is a layer of abstraction that allows developers to build functionality faster and more clearly, embedded in a specific context. Perhaps the context is what makes it different from a plain library. Libraries are generally environment-agnostic, whereas an SDK seems to combine the logic of different components into a single whole tied to a particular operating system or piece of hardware.

Sounds reasonable – though I’m still not sure if this is the right framing.

1. Exposure

The next step in building intuitive understanding seems to be increasing one’s exposure to the given term.

The idea is to see how a definition “lives” in practice – which tools or phenomena actually meet its criteria. Intuition develops when we can examine multiple instances of the same concept in reality.

Examples of SDKs include:

- Google Cloud SDK – tools and libraries for working with GCP

- Stripe SDK – tools for adding payments to an application

- Android – tools for adding SMS, voice calls, WhatsApp, etc. to apps

I deliberately choose examples closest to my “mental scaffolding” – ones I already have some experience with. For instance, I’ve worked more with GCP than with Android, so that particular example resonates more with me.

Looking through the documentation, I notice a few things:

- An SDK isn’t a single, uniform entity – there are different variants for specific contexts, e.g.,

Google Cloud SDK for GoorGoogle Cloud SDK for Python. - My initial assumption (

SDK = libraries/tools + context) seems accurate. Each example follows a similar pattern: “X – toolkit – for Y – context.” The context can be a platform (OS, hardware) or a programming language. - The “tools” in an SDK are often the API of a service, but also libraries, developer environments (like debuggers, emulators), documentation, and sometimes even ready-made plugins or project templates.

2. Play

To truly understand something, I need to move it from the theoretical-linguistic sphere into reality. Since I already know the definition and have concrete examples of how the concept “materializes” in the real world, I can try playing with one of these examples – to build “muscle memory” of applying it in practice, look at it from different angles, and tinker with it a bit.

With SDKs this is fairly simple – and in the era of vibe coding, easier than ever. I thought I’d build a small app to help me understand how and for what purposes an SDK can be used.

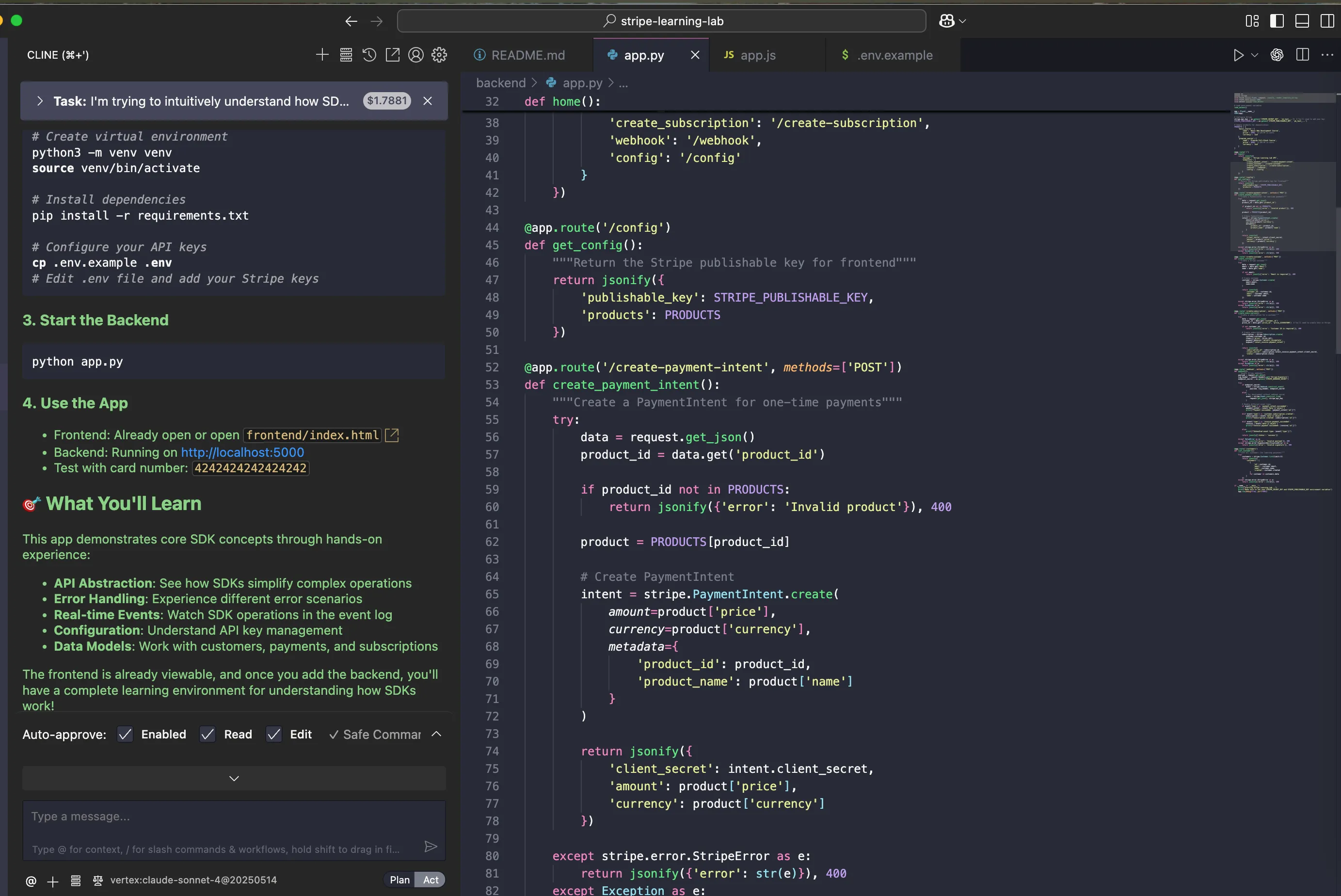

For such cases, I usually use Cline with one of the Claude models. This time, I simply asked it to create a very simple app using the Stripe SDK – so that I could read the code, understand the syntax of this specific SDK, and get familiar with the functionalities it allows you to implement.

The result was a straightforward app made up of an HTTP server and an API server:

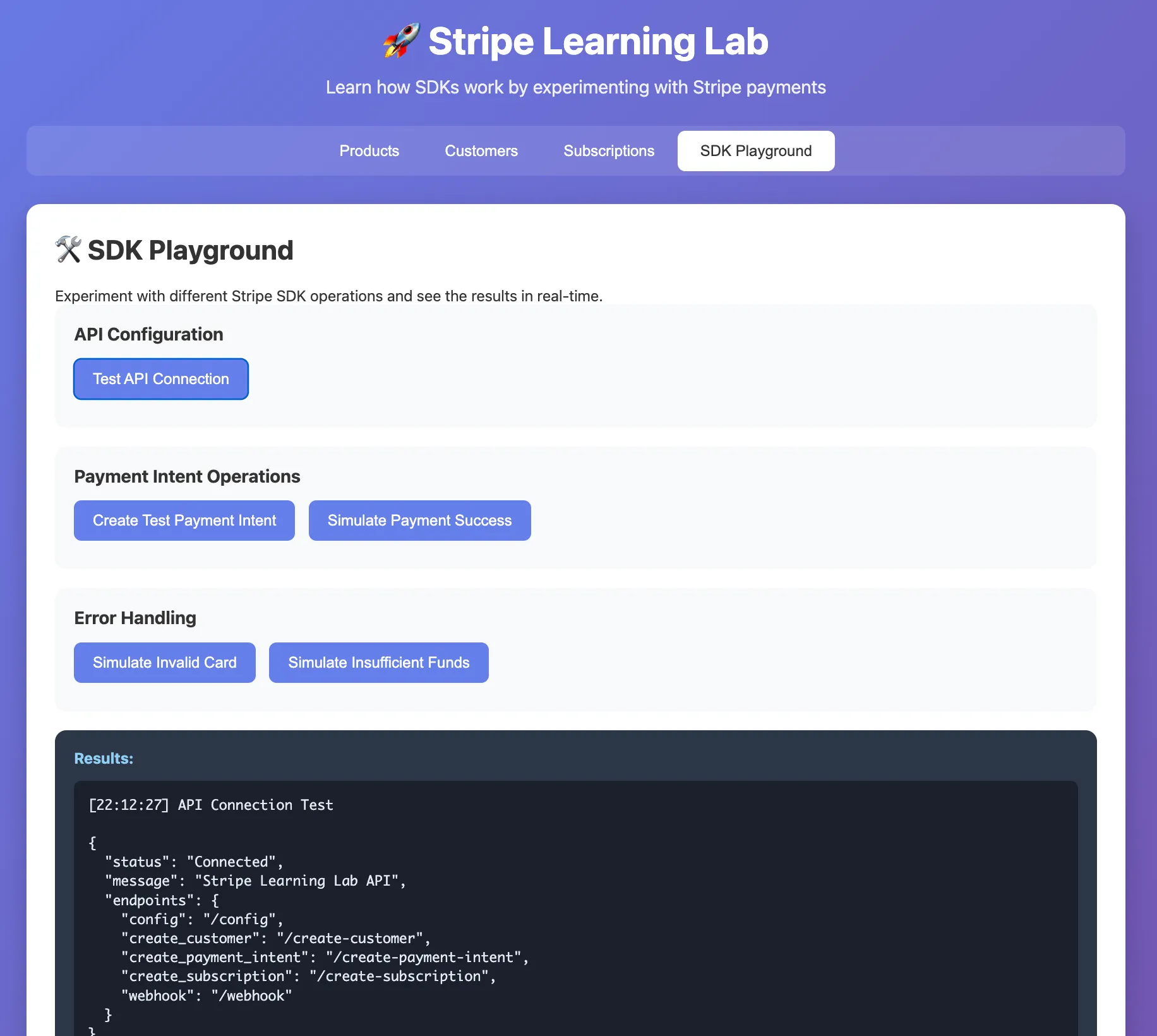

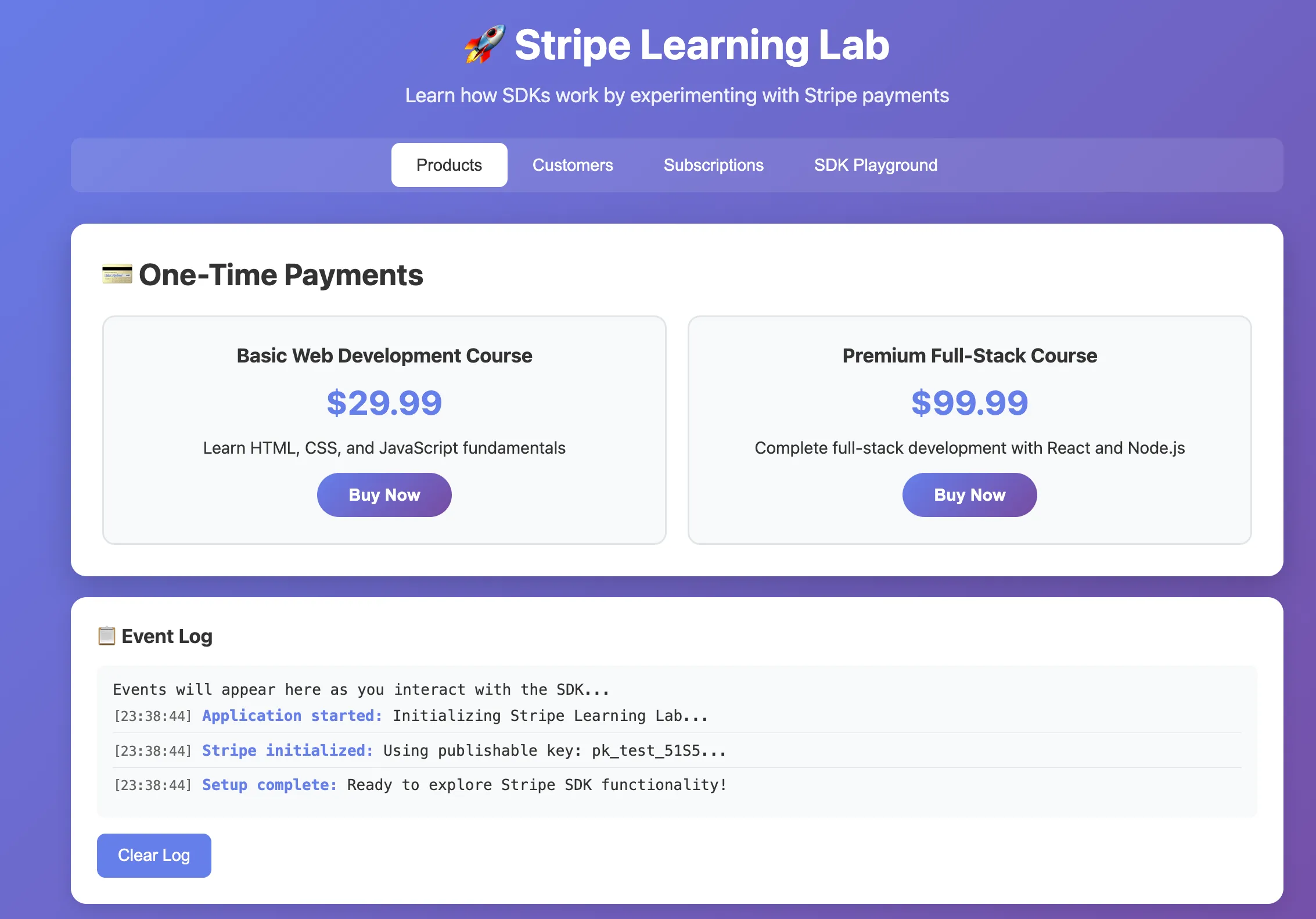

And here’s how it looked in the browser:

The app also had a mocked-up product purchase page:

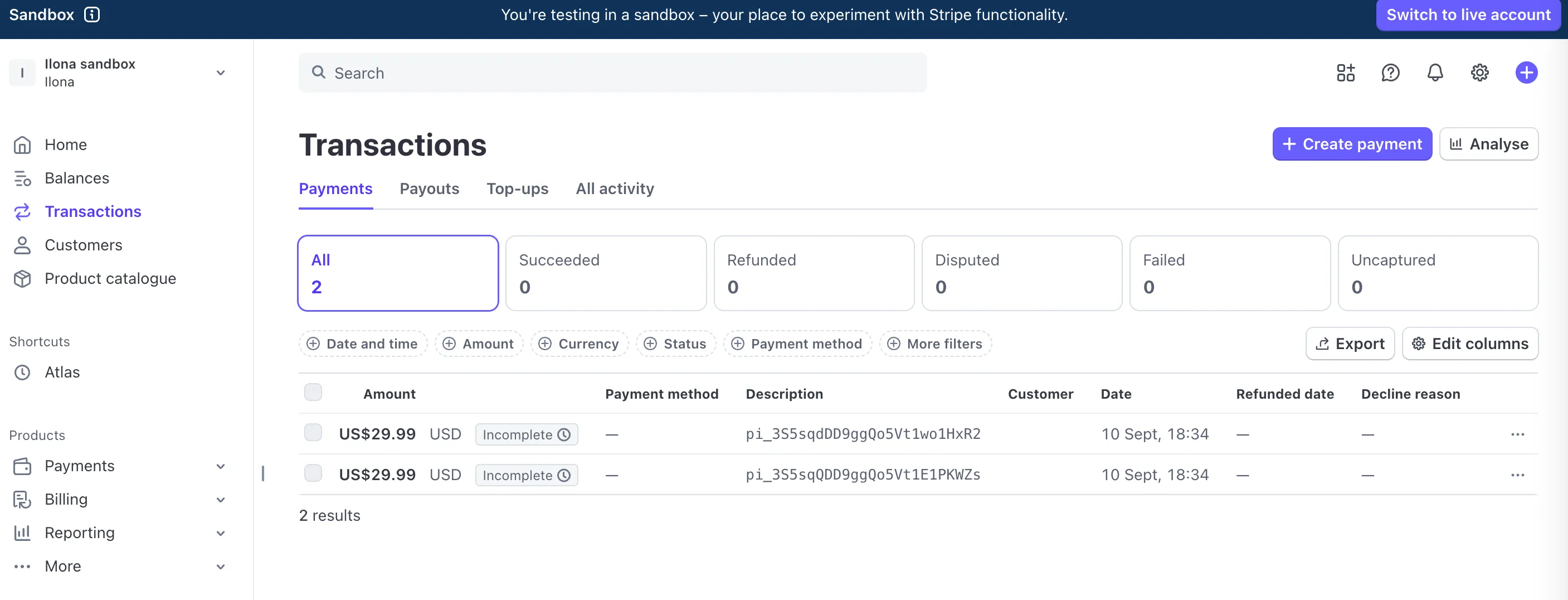

And I could see that these purchases were indeed logged on the Stripe side:

Of course, the app itself is basically “throwaway,” and the code has plenty of holes and throws errors in many places. But the core functionality works, and I’m able to trace the entire flow and understand, in practice, how an SDK is used (in this case, the Stripe SDK for Python) – and that’s enough for me. The purpose of this application is so that I can see what an SDK looks like in practice and get a sense of how it’s useful.

3. Representations

The next step toward “intuitive understanding” that ChatGPT suggested to me is trying to “translate” the idea from one form into another – for example, a drawing, a metaphor, an equation, or a story. Each transformation forces you to “recode” the concept in your mind and gives you another way to look at what you want to understand.

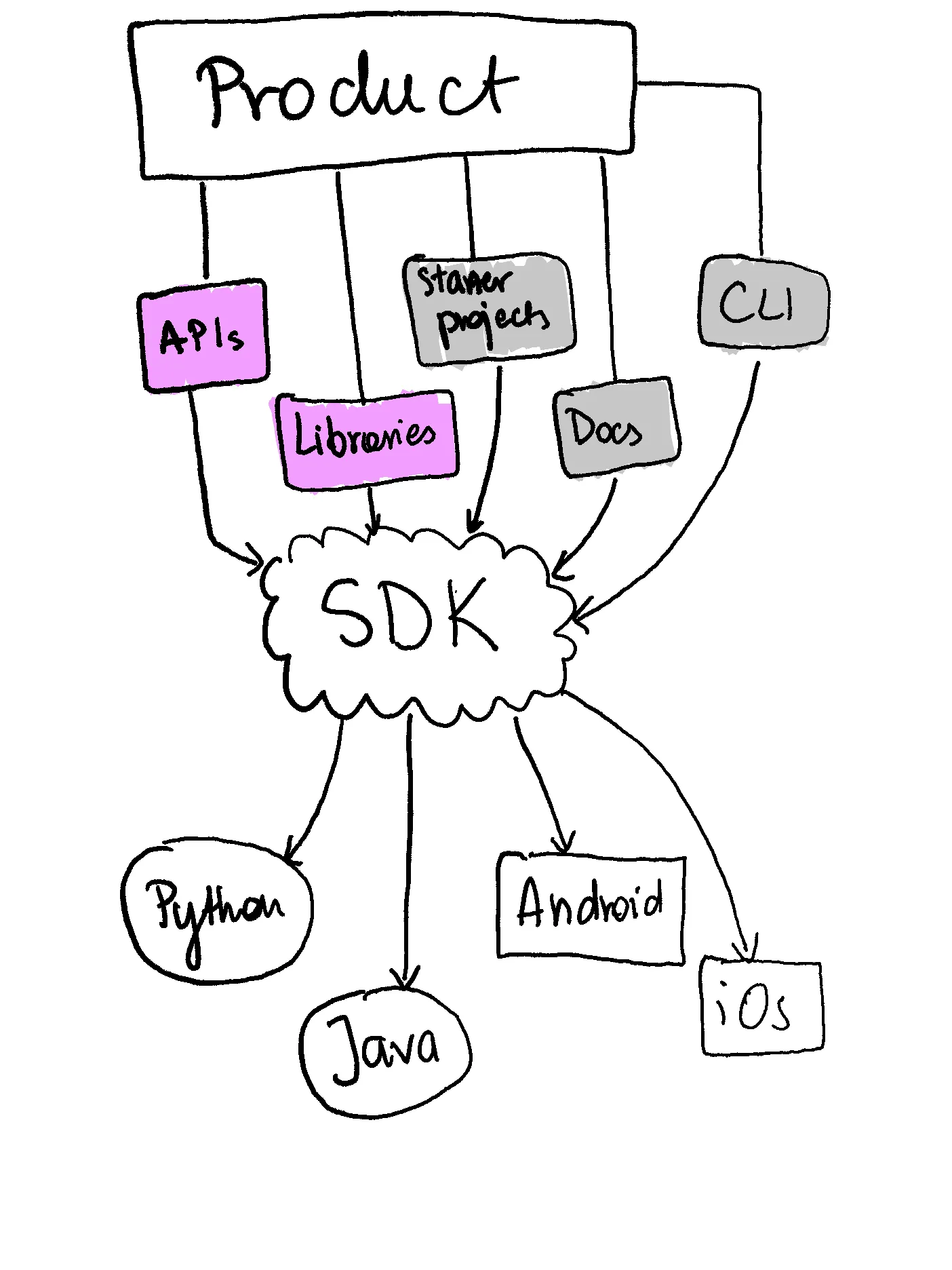

I love the “visual metaphors” of programming and design concepts created by Maggie Appleton. So, using my Remarkable, I tried drawing my own version of what an SDK is.

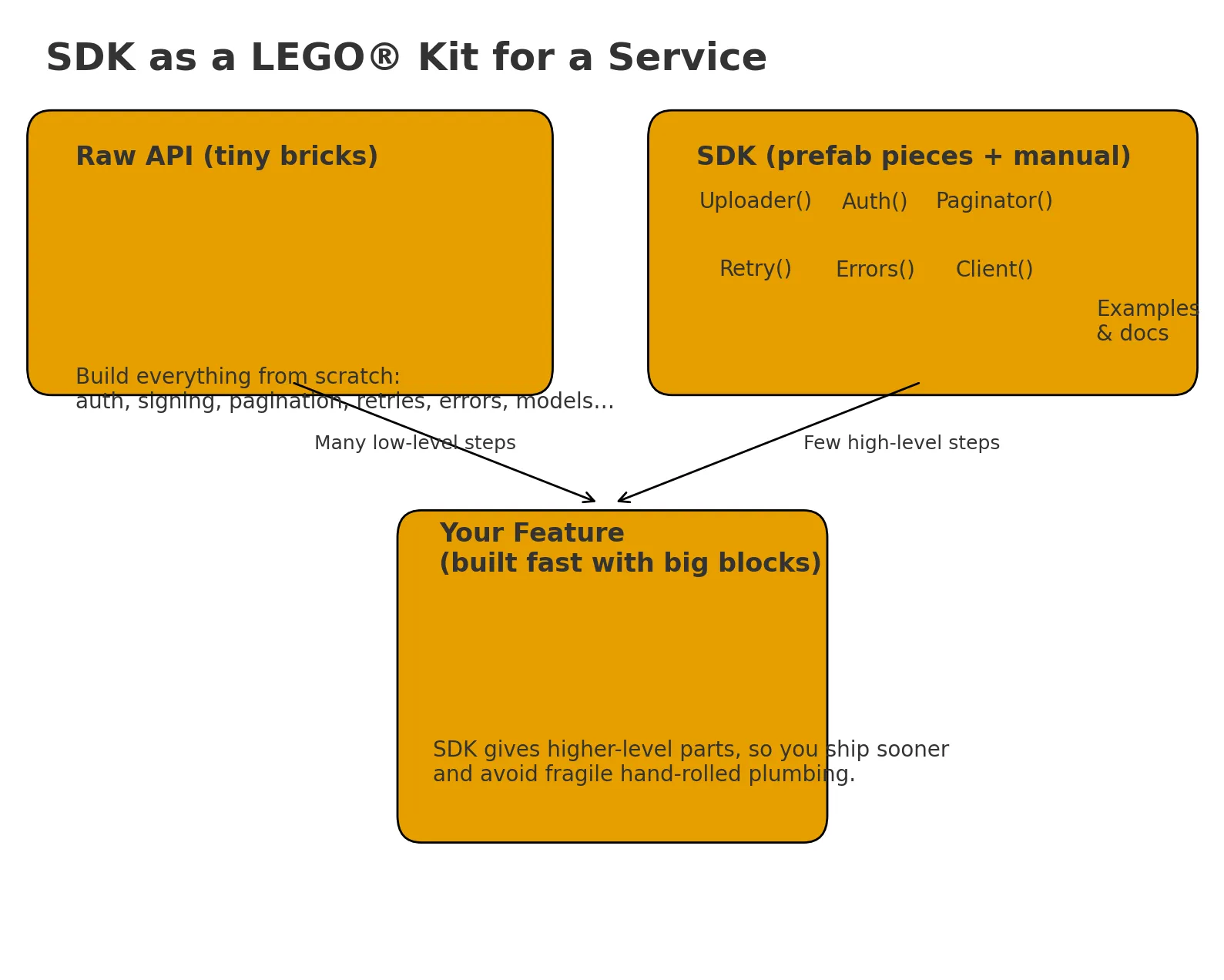

Out of curiosity, I also asked ChatGPT how it would visualize an SDK. It responded like this:

The “lego” metaphor shows up pretty often in articles explaining SDKs, so it’s no surprise that this mental model came up here.

And actually, this example illustrates what intuitive understanding is - we all “intuitively” understand what lego is, which makes it easy to transfer that concept into other contexts. My goal is to reach that same level of understanding with SDKs: to understand them well enough to spot “SDK-ness” even in phenomena that have absolutely nothing to do with programming.

I also tried playing around with Sora to generate a video-visualization of what an SDK is. After a few attempts that produced, uh… rather weird results, I finally landed on this prompt:

Please visualize what an SDK is. Don’t include any people or text in the video, but rather create an imaginary visual, artistic representation of what an SDK is. It can be abstract, yet it should feel familiar to people intuitively understanding the concept.

4. Alternatives

According to the theory of structuralism, new concepts gain meaning not so much by linking a name with a representation, but by placing that name within a context – within a system of other definitions we already know. This allows us to distinguish: X is not Y, not A, not Z.

In our case, we want to understand how an SDK differs from other, similar concepts such as a library, a framework, or an API. Once again with ChatGPT’s help:

Library – a collection of functions, classes, or modules you can call in your code so you don’t have to write everything from scratch. It’s like a toolbox – a hammer, a screwdriver. You decide when to use the hammer and when to use the screwdriver. An example is NumPy in Python – you choose when to call

numpy.array()ornumpy.dot().SDK – a package of tools provided by the creator of a platform or service to make it easier for developers to build apps in that ecosystem. Its contents include libraries + documentation + code samples + developer tools (sometimes compilers, debuggers, testers). Its goal is to simplify interaction with an external service/system. It’s not just a toolbox, but an entire IKEA DIY kit – you don’t only get a screwdriver, but also instructions, screws, glue, and sometimes even pre-built parts. An example is the Android SDK – it gives you libraries for working with Android, a phone emulator, documentation, and tools to build apps.

Framework – a skeleton (framework) into which you insert your code. A framework has its own rules, lifecycle, and conventions, and your code lives inside them. Instead of a toolbox, you have a construction site with scaffolding – you have to fit into its shape. You fill the scaffolding with bricks (your code), but the structure is already imposed. An example is Django (Python) – a web framework that dictates the app’s structure, how you define models, views, and routing.

API – an interface: a set of rules, method names, data structures that tell you how to communicate with a given system. It isn’t something material like a .dll or .so file. An API is more of a contract: “if you call this function with these parameters, you’ll get this result.” It’s like a restaurant menu. The API is the list of dishes and the ordering rules – it tells you, “to get a pizza, tell the waiter

orderPizza(size=large).” The menu itself doesn’t cook the pizza, it just tells you what you can get and how to ask for it.

5. Teaching

The Feynman Technique is probably familiar to anyone interested in meta-learning. Its essence comes down to “testing” your own understanding by trying to explain the concept to a twelve-year-old (real or imaginary), spotting the gaps, and then filling them.

So if you happen to have a twelve-year-old nearby, sit them in front of the screen and please let me know how they react to this definition:

You know what Facebook is, right? (there’s a chance I’ll fail at this very first step, since apparently it’s now only for boomers). Now imagine that on my own website I’d like to implement a feature that lets me display a few of the latest posts from my profile. If I tried to do this using only “raw” code, it would take me a long time, and I’d probably make mistakes along the way. Fortunately, Facebook provides a set of tools that allows me to implement such functionality much faster – ready-made “building blocks” that let me simply say, with a few lines of code instead of hundreds, ‘Hey Facebook, show my latest posts here.’ Since Facebook knows better how to implement this across various platforms, using their tools reduces the risk that something will break. As a platform, Facebook benefits from users building such integrations, because it boosts the platform’s popularity – hence their decision to create, maintain, and share these tools. These tools – provided by a specific platform, for a specific context (like a programming language) – are what we call an SDK.

Naturally, a few hypotheses come to mind that I’ll need to verify – for example, whether the situation I described is in fact a real example of using Facebook’s SDK? Or whether that’s really the motivation behind why platforms choose to create and maintain SDKs?

Each of these hypotheses requires verification – and that’s where the strength of this method lies. You can repeat it as many times as needed until you arrive at an explanation you’re 100% confident in.

6. Time

Even after going through this whole process and feeling that I now intuitively understand what an SDK is, I’m aware that the understanding may still be incomplete. I may be missing areas where I still lack knowledge. Intuition is a kind of “slow cooking” – the subconscious needs time, repetition, and more exposures to solidify the whole picture.

That’s why, now that I know the basics, I’ll be more alert to this concept. I’ll pay attention to other examples of SDKs, look for analogies in phenomena unrelated to programming, and build more projects using different toolkits. Step by step, I’ll deepen and refine my understanding.

Conclusion

In the end, I believe that together with AI I’ve managed to develop a reasonable framework for building intuitive understanding of various topics for my own needs.

Now, with the entire process laid out step by step, I’ll test it on new subjects – both programming-related and completely independent of programming – while continuing to refine and improve it.

Ultimately, my goal is to build my own “mental toolbox” so I can learn new topics quickly and effectively – and although AI isn’t strictly necessary in this process, as we’ve seen, it can accelerate many of these stages.